Why do Japanese ships have “maru” affixed to their names? (4)

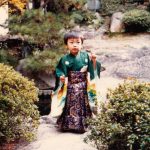

How To Fend Off Demons From Your Baby

日本語は英語の下にございます。/ Japanese translation is below the English text.

This is the fourth of the five posts on: Why do Japanese ships have “maru” affixed to their names?

=> (1) Japanese Ship Names Often End With “Maru”

=> (2) “Maru” is a Symbol of Perfection

=> (3) “Maru” in the Names of Other Things

(4) How to Fend Off Demons From Your Baby

=> (5) Modern Japanese Ship Names and “Maru”

HOW TO FEND OFF DEMONS FROM YOUR BABY Contents 1) Sickly infants 2) Demons stay away from filthy things 3) “Maru” meaning “dung” 4) The Hokkaido Ainu people 5) "Maru" as a talisman to protect precious properties

1) Sickly infants

In olden days, people in Japan suffered from a very high death rate of babies and small children.

There was a saying “Nanatsu mae wa kami no uchi (Before seven, it is partially a god)”.

It meant that before turning seven years old (today’s five or six years old), a child was so sickly and feeble that they considered it as a kind of spirit that demons, gods, or evil spirits could take to their world at their will.

Parents naturally desired to protect their children and raised them very carefully until they were big and strong enough.

One popular way to protect their babies from demons was to give them names meaning something very dirty and befouled.

In those days, words had even stronger power than today. So, if they called their children something dirty, it meant that they WERE the dirty thing.

Humans hated dirty things, so must demons, people believed; demons would be disgusted to be near such things. If people could thus deceive them, their children would stay healthy and happy.

2) Demons stay away from filthy things

From the Heian through Edo Era (794-1867), children of various castes were first given a “childhood name”. They bore that until they reached their adulthood, 13 to 16 years old depending on the time, area, profession, etc.

This childhood name sometimes included “kuso” meaning “dung” directly.

A famous example is “Ako-Kuso (My Child Dung)”, the childhood name of Ki no Tsurayuki, a renowned author, poet, and court noble of the 9th Century.

Also, there is a female poet whose name was Minamoto no Kuso, whose poem appears in Kokin Wakashu, a Heian Era’s imperial anthology of poetry.

3) “Maru” meaning “dung”

“Kuso” means “dung” or “shit” in today’s Japanese, too. People don’t often use it today because it sounds so direct. If they ever do, it is usually to curse, express vexation or encourage oneself in a very rough manner.

Incidentally, “maru”, now only recognized as “round”, had another meaning as dung or to excrete in the past.

Therefore, there is a view that “maru” or “maro” at the end of so many boys’ names had the same function as “kuso”, a talisman to fend off the demons.

I am a native speaker of Japanese, but when I first heard this theory, I didn’t know what to think; “maru” only has the meaning of a round shape today. Then, I remembered a common word “o-maru”.

“O-maru” is a portable toilet, particularly for toddlers. I thought the shape of the round bowl was the namesake, but if “maru” meant to excrete, it is more straightforward.

It is said that in the ancient imperial court, they used lacquered and gold-leafed gorgeous chamber pots. Ladies-in-waiting began to call them “o-maru”, adding the prefix “o” for politeness. With time, the word spread among the commoners’ society.

In Japan, people in different areas speak different dialects, and some old words and expressions are scattered in them. I had never heard it in Kanto Region where I grew up, but I read that people still use “maru” for going to the bathroom, in such areas as Kumamoto, Oita, Nagasaki, Fukuoka, which are all on Kyushu Island, and Nagano, Gifu, Aichi, Mie, and Shimane outside of it.

4) The Hokkaido Ainu people

The custom of naming a child after a dirty thing to fend off the demons also existed among the Ainu people in Hokkaido.

Today, most Ainu are intermarried to Japanese of other ancestries, many live outside of Hokkaido, and give their children a common Japanese name.

However, in olden days, the Ainu believed that the sickness was evil spirits who entered into a child’s body because they loved pretty things. Ainu believed that evil spirits hated dirty things, so they gave their infants such names as “Teinepu (a wet thing)”, “Pon Shon (small shit)”, and “Shontaku (lump of shit)” hoping that they would stay away.

Sickly children and children with beautiful facial features were in particular danger. Not only demons wanted to snatch them but also good gods wanted to take them to heaven. For these kids, the parents needed stronger protection, and had to come up with dirtier names such as “Turushino (covered by filth)” and “Ekashiotonpui (the anus of an old man)”.

They even named a baby “Resaku (nameless)” so that that baby doesn’t exist in theory.

The Ainu people didn’t leave written records, but we can peep into their custom and way of thinking in the Japanese government’s records from the Edo Era and earlier. Some believe that the Ainu kept custom and beliefs of the more ancient people living in Japan who didn’t surrender to the authority of the emperor of Japan until the 11th century.

5) “Maru” as a talisman to protect precious properties

There is not much evidence to support any of these wildly different opinions more than others.

However, it seems to us that the origin of “maru” in the names of ships may be the same as those of precious properties, i.e., swords, musical instruments, dogs, horses and heirs. And that “maru” was a suffix working as a verbal talisman to protect the bearer of the name from demons and misfortune that they cause.

★ Please continue reading: => Modern Japanese Ship Names And “Maru”

[End of the English post]

なぜ日本の船名には「まる」が付くのか?(4)

赤ちゃんを魔物から守る方法

ここまでのお話はこちら:

=> (1) 「マル・シップ」~日本の船名に「まる」が多くついていること

=> (2) 「まる」は完全の象徴

=> (3) 他のものの名につく「まる」について

もくじ 1) ひよわな赤ん坊 2) 魔物は汚らしいものを避ける 3) 「くそ」を意味する「まる」 4) 北海道のアイヌ 5) 「まる」は財産を守る護符

1) ひよわな赤ん坊

昔の日本では幼い子供の死亡率がとても高く、人々の悩みの種でした。

「七つ前は神のうち」という言葉があります。

7歳(今日の5、6歳)になる前、子供というものは非常にひ弱で病気がちで、何かの精霊のようなものである。だから、魔物たちや神々が好きな時にさらっていくことがある、この言葉はそのような考えを表しています。

もちろん親たちは、子供たちが大きく強くなるまで一所懸命大切に育てました。

魔物から守るために、大変汚らしいものの名前をそのまま子供に与えるということもよくやりました。

その頃、言葉は今日よりもっと強い力を持っていました。そのため、子供たちを汚いものの名前で呼べば、子供たちは汚らしいものそのものに「なった」のです。

人間は汚いものが嫌いです。だから、魔物もぜったいそうで、汚らしいものの近くになど寄りたくないはずです。人々はこうして魔物たちを欺くことができれば、子供たちは健康で、幸せに暮らせると考えました。

2) 魔物は汚らしいものを避ける

平安時代から江戸時代まで、階級に関わらず子供たちは「幼名」を与えられ、成人する時までその名で呼ばれました。成人年齢は時代、地域、職業によって異なりましたが、13歳から16歳です。

この幼名には時として大便を意味する「くそ」が入っていました。

有名な例は9世紀の高名な詩人で官僚だった紀貫之の幼名、「阿古久曽」(私の子、くそという意味)です。

また、源久曾という女性の詩人もおりました。平安時代の勅撰和歌集『古今和歌集』に歌が載っている人です。この人は大人になっても「くそ」と呼ばれていたことになります。

3) 「くそ」を意味する「まる」

「くそ」は現代の日本語でも同じ大便という意味です。ただ、とても直接的な表現なので、あまり使いません。使うなら、相手を罵ったり、苛立ちを表現したり、荒っぽく自分を奮起させたりする場合です。

さて、現代では「円のかたち」としか考えられていない「まる」ですが、昔はくそ、あるいは排泄するという意味がありました。

したがって、多くの男児の名前に付く「まる」「まろ」は、「くそ」と同じく魔物をやり過ごすお守りだったという説があります。

私の母語は日本語ですが、この説を知った時、よくわかりませんでした。「まる」には、円の形という意味しかないからです。その後、「おまる」というよく使う言葉を思い出しました。

「おまる」は幼児のための携帯用便器です。私は、便器が丸っこいので「おまる」と呼ばれるようになったのだろうと思っていましたが、「まる」が排泄するという意味であれば、もっとはっきりします。

古代の朝廷では、金箔をほどこした漆塗りの豪華な便器を使っていたそうです。女官たちはこれに丁寧を表す接頭語「お」を付けて「おまる」と呼びました。時につれて、それが庶民社会にも広まったというのです。

日本語の方言には古い言葉や表現が散りばめられています。関東地方では聞いたことがありませんが、地方によってはお手洗いに行くことを「まる」と呼ぶと読んだことがあります。その例は、九州の熊本、大分、長崎、福岡、それから長野、岐阜、愛知、三重、島根などにありました。

4) 北海道のアイヌ

子供に汚らしいものの名を与えて魔物を防ぐ習慣は、北海道のアイヌの人々の間にもありました。

今日、アイヌ民族の多くは異なる祖先を持った日本人と結婚し、北海道の外で暮らし、子供たちには良くある日本の名前をつけます。

しかし、昔、アイヌにとって病気は邪悪な精霊でした。彼らは綺麗なものを好むので子供の体に入ってくるのです。アイヌは、悪霊は汚らしいものを嫌うと信じて、乳児に「テイネプ(濡れたもの)」「ポン・ション(小さな糞)」、「ションタク(糞の山)」などの名前をつけ、魔物が近づかないようにと願いました。

病弱な子や、顔立ちの綺麗な子は、もっと危険でした。悪霊がさらいたくなるだけでなく、善い神々も天国へ連れていきたがったからです。そのような子供は、もっと効力の強いお守りが必要だったので、親たちは、もっと汚い名前、「トウルシノ(汚ないものまみれ)」「エカシオトンプイ(老人の肛門)」などを思いついたのでした。

「レサク(名前がない)」と名付けられた赤ちゃんもいます。そうすれば、理論上はその子は存在しませんから。

アイヌは文字で書かれた記録を残しませんでしたが、江戸時代やそれ以前に幕府にが残した記録で、アイヌの慣習や考え方をのぞき見ることができます。アイヌ民族は11世紀に日本の天皇に征服されるまで、日本に住んでいた、より古い民族の慣習や考え方を維持していたとも言われています。

5) 「まる」は財産を守る護符

これら全然ちがった説のどれをも、確固と支える証拠はありません。

しかし、船名の「まる」の起源が、剣や楽器、犬や馬、後継者など大切な財産の名についた「まる」のそれと同じと考えることは、あまり無理がないと思います。すなわち、「まる」はもともと、その名を持ったもののお守りとなる魔除けの言葉であったと。

★ 続きはこちら: => 現代日本の船名

[和文部終わり]