ルビ付き和訳は英文の下にございます。/ The Japanese translation is below the English text and fully rubied.

Canada and the Satsuma Mandarin

Contents 1. The importers of Citrus Unshiu 2. Christmas oranges in Canada 3. The nicknames 4. The Japanese emigrants in the Meiji Era 5. The salmon fishing in Steveston 6. The emigration of the Wakayama folks 7. The “American Village” 8. Mandarins from Wakayama 9. The posterity in Steveston 10. Mr. KUNO Gihei 11. The Museums in Two Villages The Japanese translation References / 参考資料

1. The importers of Citrus Unshiu

Which countries do you think are the major importers of Citrus Unshiu or the Satsuma mandarin from Japan?

According to the most recent foreign trade statistics*1, in 2019 and 2018, Hong Kong imported the most mandarins. No. 2 was Taiwan, and No. 3 was Canada. We expected another Asian country to be in the third place, so it was a small surprise to see Canada.

Actually, Canada was the constant, and by far the largest importer of Citrus Unshiu from Japan from 1988 through 2017*2. The percentage of the fruit Canada imported in these years was always well above 50% of total Japanese exports. It sometimes exceeded 90% while countries in the second and lower rankings varied depending on the year.

Why do Canadians import so many Japanese mandarins?

*1 Mandarins and tangerines are classified as one item. However, we consider it represents Citrus Unshiu because few other kinds of mandarins and few tangerines are grown in Japan.

*2 The oldest available statistics were from 1988. However, we think Canada imported even more mandarins in the earlier period. The reason is that the total number of mandarins and the number exported to Canada both kept declining from 1988.

2. The Christmas orange in Canada

In Canada, particularly in the western provinces, people often call Citrus Unshiu the Christmas orange.

By reading some blogs, we can have a glimpse of the Canadian childhood with fond memories of Christmas oranges. For example:

- There is no fruit harvest in winter in Canada, so fresh fruits arrive from abroad by boat or railroad after the season of apples and pears. One such precious fruit was Cistrus Unshiu from Japan.

- At the beginning of December, a Japanese ship would arrive at the Port of Vancouver. It was loaded with crates of mandarins. Until the end of the 1980’s, local newspapers would announce the arrival of the first shipment of “Japanese Oranges” on the front page. The sudden emergence of bright orange color in storefronts and in homes would liven up their Christmas spirit.

- And on Christmas morning, they would always find a mandarin in the toe of their stocking which had been hung for the occasion.

- They would place the boxes of mandarins in a cold part of the house such as the laundry room. They ate them reading books in a warm room, and occasionally they went to the cold storage room to bring more mandarins back.

- The mandarins were packed in very sturdy wooden crates, so people would reuse them in many ways. Some made them into toy-boxes or toolboxes, and others footstools and small stepladders.

- Also, each fruit came wrapped in thin green or pink paper, so children could play with it, too…

3. The nicknames

Until the mid-20th Century, one of the popular nicknames of Citrus Unshiu was “the Japanese mandarin”.

However, when World War II broke out, the ships with mandarins ceased to come from Japan, which was now the enemy of Canada. At the same time, Canadians felt like avoiding the name “Japanese mandarins.”

Today, in Canada, “Christmas oranges” or “mandarine oranges” are the nicknames for all mandarins including Citrus Unshiu, tangerines and the most popular clementine. When they need to mention Citrus Unshiu alone, they call it the Satsuma mandarin.

By the way, the first Citrus Unshiu introduced to Canada was not from the Satsuma area. It was brought from Wakayama, traditionally the most famous area for mandarin production. The Wakayama mandarins came to Canada in the following situation:

4. The Japanese emigrants in the Meiji Era

This is a story of the Japanese who went abroad to work from the end of the 19th Century.

In the Meiji Era, Japan tried to build a unified, modern nation, and aggressively adopted Western technology and culture. As a result, the society changed a lot, and the people became much more mobile.

Traditionally, there were many farmers in Japan. In a typical farming family, the oldest son inherited his parents’ farm, got married and had his own family.

His younger brothers also wanted to have their own families, but they couldn’t easily obtain farmland. So, they went to big cities to find work in other businesses.

Their supposed dream was to save up money, return to their hometown to buy a property and run a farm like their big brother.

Most of them found jobs in big cities like Tokyo and Osaka, but some went abroad with the same dream.

5. The salmon fishing in Steveston

Thus, in Vancouver, Canada, a small number of Japanese began working in the late 19th Century. They worked in such industries as lumber, fishery and agriculture.

One day in 1888, a newcomer at a lumber mill in Vancouver asked his senior workers:

I am a carpenter from Mio, Wakayama. My fellow villagers are fishermen, but these days they can’t make enough money. My cousin is a sailor, and he told me that there might be fishing jobs in Sutebusuton near Vancouver. Actually, I came over to see if that’s true. Do you know anything about that place?

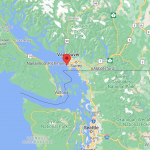

Steveston, that he called Sutebusuton, was a small fishing village located about ten miles south of Vancouver. Like Vancouver, it belonged to the province of British Columbia, and it was where the Fraser River flowed into the Pacific Ocean.

When he visited Steveston, he saw a breathtaking sight; innumerable sockeye salmon were running up the estuary. It was right in the season of the salmon run.

This was exactly what he had looked for. He wrote to his village: Salmon run up one after another as if they welled from the sea. This must be the place where all of us could have a job.

Back in his home village, some opposed the idea of sending many men all the way to Canada. However, people needed a job. Also, this man was a well-known master carpenter in the area. Maybe people could trust his integrity and judgment.

Groups of men began to sail to Steveston from the next year.

6. The emigration of the Wakayama folks

www.vancouverisawe

some.com/history/how-bcs-multicultural-fishing-industry-shaped-the-province-photos-1933780

History tells us this emigration was a great success for the folks from Wakayama. Steveston bustled with fishery and cannery operations, and the Japanese laborers were able to send money generously to their families in Mio and other hometowns.

In 1900, two thousand Japanese workers had already moved in. The sudden increase in the number of Japanese immigrants in Steveston and other parts of the province of British Columbia was such that it even caused anti-Japanese sentiments among local Canadians. They exploded in a riot in Vancouver in 1907.

In order to keep peace in British Columbian society, Canada and Japan made a “gentlemen’s agreement” the next year. Under its terms, basically, the Japanese government agreed to voluntarily limit the number of Japanese immigrants to Canada to four hundred men per year. Fortunately, however, people from Mio were treated as an exception and not included in this number. Maybe salmon fishing was a very important business for British Columbia and they needed a hand.

Before long, some immigrants wanted to have a family in Steveston. Since this agreement didn’t put a restriction on the wives of immigrants, a lot of women began migrating to Canada. An immigrant could ask his relatives in Japan to send a photo of a single woman and make a decision to marry her. The “wife” prepared documents to prove their marriage before leaving Japan, and the man greeted his “picture bride” in Vancouver.

When their kids were six years old or so, many parents sent them alone to Japan to live with their parents. This way they could go to and advance in the Japanese schools.

Others chose to raise children and stay permanently in Canada. It was not easy either since for some period, not everyone, particularly immigrants, were able to have education in Canada.

The presence of the laborers from Wakayama continued until World War II broke out. In 1940, two thousand workers were in Steveston and it was more than the population in Mio.

7. The “American Village”

Some Japanese got used to the Canadian way of living and felt very comfortable.

Therefore, when they retired and returned to Mio, they built houses according to their preferred style of living. Besides traditional Japanese houses, some were houses in an eclectic Western-Japanese style. Others in a more Western style with real glass panes for windows.

travel.co.jp/guide/

article/44199/

Thus, Mio became a village with wealthy retirees from Canada, and people enjoyed life with nice bits of Western culture. For example, they sat on a chair and ate at a dining table. They put on a coat and a hat when going out. They listened to music on a gramophone when they relaxed, and slept in a bed. English words and expressions were often heard in conversation.

Mio had such an exotic, fashionable atmosphere that people in the vicinity dubbed it “Amerika-mura” (the American Village). Of course, it came from Canada, but people thought on the other side of the Pacific was the American Continent.

8. The Mandarins from Wakayama

In winter, the Japanese in Steveston had their families in Japan send mandarins to them from Wakayama. Then they enjoyed eating mandarins and decorating rice cakes, and celebrated the New Year as they used to do in Japan.

Another name for Wakayama was Kishu in Edo Era. The area was very famous for producing small, sweet mandarins called “Kishu mikan” (Citrus Kishu). However, in the late 19th Century, they produced more and more seedless Citrus Unshiu along with Citrus Kishu (Please refer to “What is “Satsuma” mandarin?”).

So, in Steveston, they happily and proudly shared their mandarins with their friends. This blended into the Canadian custom of Christmas oranges.

As early as 1891, a Canadian trading company began importing the Japanese mandarins. It continued each year except during WWII and several subsequent years. And this is how Canadians came to be accustomed to seeing a Japanese ship in the Port of Vancouver every December and feel it like the harbinger of Christmas.

9. The posterity in Steveston

The early Japanese workers in Steveston had a hard time learning English. So did their children when they went to Canadian schools. On the contrary, exactly because they were fluent in Japanese, they frequently exchanged letters and gifts with their families in Mio and other areas. Not only did they visit Mio but also they received visits from Japan.

As the grandchildren of the first-generation immigrants grew up, they spoke English as their mother tongue and they considered themselves Canadians. It took time for Canada to embrace Asian immigrants in its society, but after WWII, Japanese Canadians were given the full Canadian citizenship including the suffrage, and the Canadian government issued formal apology and redress to Japanese Canadians for what they endured during WWII.

More recent generations know their root is in Mio or another village in Japan, and occasionally take a trip there. But it seems there are few personal relationships between them and their family in Japan. They come against the language barriers.

10. Mr. Gihei KUNO

The name of the master carpenter who invited his fellow villagers in Mio to Steveston was Gihei KUNO.

Called the Father of the Japanese immigrants to Canada, Gihei is remembered for his achievement of making arrangements so that the folks from Wakayama could live and work in Steveston. He himself ran a Japanese grocery store and an inn and took care of the immigrants for nearly twenty years.

Gihei was the first emigrant to Steveston from Mio, but he left his wife and children in Mio. He worked so hard to help men in Steveston that one day he briefly visited his home in Japan to find his wife had left home and been married to another man.

Winters in Canada are severe, and Gihei suffered from rheumatism.

As his conditions got worse, he handed his business to his relatives and returned to Japan. He was 57. Six years later, he passed away in Wakayama. They say he wished to visit Steveston again to his last day.

11. Museums in Two Villages

A Canadian man visited Mio in 2009 and wrote about his trip on a website. His grandfather emigrated from Mio to Steveston in the late 19th Century.

In Mio, the lush forested mountains closely surrounded the small bay and reminded him of the British Columbia mountains on the Pacific. He imagined the folks from Wakayama felt affinity for Steveston for its view.

One of the places he visited in Mio was “Canada Shiryo-kan” (the Canadian Museum). On display were various artifacts brought back from Canada. Old steamer trunks, a lumberjack shirt, kitchen tools, old photos, children’s essays and clothes given to the Japanese immigrants when they were put into the internment camp during WWII and such tell their lives, and someone even brought back some coastal First Nations pieces such as a totem pole. The purpose of the display was to tell people the ordeals of the Japanese immigrants, and it seemed there was no or very little explanations on each item in English.

This museum closed in 2015 and another organization opened “Canada Museum” in 2018. It is actually a renovated, small, elegant, Western-style house built by a retiree from Steveston. We couldn’t find any English page on their website (in May 2021).

In Steveston, the historic small “Japanese Fishermen’s Benevolent Society Building” still stands. Their exhibits, websites of Canadian Government, Canadian Museum of Immigrants, All Canadian Japanese Association, local media and Japanese media tell the stories of Gihei KUNO and the workers from Japan. Much is available in English and some in Japanese.

There were a lot of interesting stories about the Japanese immigrants to Canada. One day we would like to visit Mio and Steveston, and look for some more.

[End of the English post]

カナダと温州みかん

目次 1. 温州みかんの輸出先 2. カナダのクリスマス・オレンジ 3. みかんの呼び名 4. 明治の日系移民 5. スティーブストンの鮭漁 6. 和歌山びとの集団出稼ぎ 7. アメリカ村 8. 和歌山のみかん 9. カナダ生まれの子や孫たち 10. 工野儀兵衛 11.二つの村の資料館 参考資料

1. 温州みかんの輸出先

日本の温州みかんの輸出先は、主にどんな国だと思いますか。

貿易統計*1によれば、最近2019年、2018年は、一位が香港、二位台湾、三位カナダ。三位は他のアジアの国を予想していたので、少し意外でした。

しかし、カナダは、1988年から2017年まで常に最大の輸出先でした*2。他の国よりずっと多く、個数でつねに50%以上、時には90%以上を占めていました。二位、三位の国は年によって変わります。

なぜカナダでこんなに日本の温州みかんを輸入してきたのでしょうか。

*1 マンダリン・タンジェリンと併せて一つの品目になっていますが、日本ではタンジェリンはほとんど栽培されていないので、ここでは温州みかんと考えます。

*2 1988年以前の統計結果が入手できませんが、これ以前はもっと多くがカナダに輸入されていたと思います。輸出総個数も、カナダへの輸出個数も、1988年から一貫して減り続けているからです。

2.カナダのクリスマス・オレンジ

カナダ、特に西部では、よく温州みかんを「クリスマス・オレンジ」と呼びます。

カナダの人々のブログを読むと、クリスマス・オレンジと共にあった楽しい子供時代をのぞき見ることができます。曰く、

- カナダは冬に果物が穫れないので、リンゴや梨の季節の後、果物は船か鉄道で外国から来るものに限られる。その貴重なひとつが日本から船で運ばれて来るみかんだった。

- 12月初めになると、バンクーバー港にみかんの木箱を満載した日本の船が着く。1980年代末頃までは、みかん船の到着は地元の新聞の第一面で報道されたものだ。華やかなオレンジ色のみかんが店先や食卓にいっせいに現れ、クリスマス気分が盛り上がった。

- そして、クリスマスの朝は、吊るしておいた靴下のつま先に必ずみかんが入っていた。

- 洗濯場など寒い所にみかん箱が置いてあった。暖かい部屋でみかんを食べながら本を読んで、なくなると寒い部屋から取ってきて、また食べた。

- 昔は頑丈な木箱に入ってきたので、空き箱を再利用して、おもちゃ箱や道具箱、低い椅子、踏み台を作ったりした。

- みかんが緑やピンクの薄紙で包まれていたので、その薄紙で遊んだりもした、などなど……

3.みかんの呼び名

20世紀前半のカナダでは、温州みかんを「ジャパニーズ・マンダリン」とも呼びました。

しかし太平洋戦争が始まると、カナダの敵国となった日本からみかん船は来なくなり、ジャパニーズ・マンダリンという言葉も聞かれなくなりました。

現在、「クリスマス・オレンジ」「マンダリン・オレンジ」が、温州みかん、タンジェリン、クレメンタインなどをまとめて呼ぶ言葉になっています。温州みかんを特定する必要があるときは「サツマ・マンダリン」と呼ぶようです。

ところで、カナダへ最初に入った温州みかんは、薩摩ではなく、和歌山という、まったく違った場所で穫れたものでした。これには、次のような経緯があります。

4.明治の日系移民

これは、19世紀末に海外へ働きに出た日本人たちの話です。

明治時代(1868~1912)、日本は統一された「近代国家」を築こうと積極的に欧米の技術や文化を採り入れました。その結果、社会に多くの変化が起おこり、人々の生活で移動・移転することが多くなりました。

もともと日本は農家が多く、長男が家の農業を継ぎ、結婚して家庭を持ちました。

弟たちも、結婚して家庭を持ちたい。しかし、農地がなかったため、出稼ぎに行きました。

いつかお金を貯めたら故郷へ戻って土地を買い、長兄と同じように家庭を持って農業を営むことが夢とされました。

出稼ぎ先は東京、大阪などの大都市が主でしたが、同じ夢を持って海を渡った人々もいたのです。

5.スティーブストンの鮭漁

こうして、カナダのバンクーバーでも、19世紀後半から少しずつ日本人が材木業、漁業、農業などの分野で働くようになりました。

1888年のある日、バンクーバーの製材所に加わった新顔の日本人が、先輩たちに尋ねました。

自分は和歌山、三尾村の大工だ。村の生業は漁業だが、このごろ金にならなくてみんな困っている。船乗りの親戚が、バンクーバーの近く、すてぶすとんという所には漁師の仕事があるかもしれないと言っていた。実はそれで見に来たんだが、すてぶすとんって、知っているか?

男がすてぶすとんと呼んだのは スティーブストン(“Steveston”)村。バンクーバーと同じくブリティッシュ・コロンビア州にあり、バンクーバーの南約15キロ、フレーザー河が太平洋に注ぐ地点の小さな漁村でした。

たまたま紅鮭の遡上の時期で、男がスティーブストンを訪れると、息をのむような光景が目に入りました。数えきれないほどの鮭が広大な河口を上っていたのです。

男は、これこそ自分の求めていた新天地だと感じました。早速村へ手紙を認め、次から次へと鮭が川を上っていく様子は、まるで泉に水が湧くようだと伝えました。これなら、きっとみんなに仕事があるだろうと。

村では、男たちの集団出稼ぎについて、反対もありました。しかし、失職者は多く、男は郷里では知られた棟梁でした。あいつが言うなら確かだろうと思わせた、人となりもあったでしょう。

さっそく翌年1889年から村民たちが集団で渡航するようになります。

6.和歌山びとの集団出稼ぎ

振り返ってみると、この集団出稼ぎは和歌山の人々にとって大成功でした。スティーブストンは鮭漁や鮭缶づくりで繁盛し、出稼ぎ者は、三尾など郷里の村へ潤沢な送金ができたからです。

1900年にはすでに二千人の日本人がスティーブストンに移住していました。当時、ブリティッシュ・コロンビア州各地への日本人移民が急増し、現地では反日感情が高まって1907年にバンクーバーで暴動が起きたほどでした。

ブリティッシュ・コロンビアの社会不安を鎮めるため、日本とカナダの間で紳士協定が結ばれました。日本政府はこの後、基本的に年間男性400人しかカナダに移民許可を出さなくなったのですが、幸い、三尾出身者は別枠扱いだったといいます。ブリティッシュ・コロンビアでもスティーブストンの鮭漁は重要な産業で、人手が必要だったのかもしれません。

やがて、スティーブストンで家庭を築きたい人が出てくると、「写真花嫁」という方法が採られました。配偶者は移民許可の制限対象でなかったので、日本の親戚などに独身女性の写真を送ってもらって心を決め、その女性に出国前に結婚手続きをしてもらって、バンクーバーで妻として迎えたのです。こうして、多数の日本人女性がカナダへ移住しました。

夫婦が子供を持つと、多くは就学年令に達する頃子供だけを日本へ送り、祖父母に養育してもらいつつ日本の学校へ行かせました。

一方、家族でカナダへの永住を選んだ人々もいます。カナダでは移民は教育が受けにくい時代があり、これも容易ではありませんでした。

このような集団出稼ぎは太平洋戦争開戦時まで続きました。1940年にもスティーブストンに二千人の出稼ぎ者がいたといいます。三尾の人口が二千人もなかった時代です。

7.アメリカ村

このうち、ある人々は、カナダの生活スタイルにすっかり慣れ親しんでしまいました。

そのため、引退して三尾に帰った人たちの建てた家は、日本建築だけでなく、和洋折衷型の建築だったり、ガラス窓のはまった洋館だったりするのです。

出稼ぎ者の引退村のようになった三尾で、人々は洋風を混じえた豊かな生活を楽しみました。食事にテーブルと椅子を使い、外出にはコートと帽子を身に着け、蓄音機でレコードを聴き、ベッドで眠る。また、会話では頻繁に英語の単語や表現が聞かれました。

このようなハイカラな雰囲気のために、三尾は「アメリカ村」と呼ばれるようになりました。もちろんカナダなのですが、太平洋の向こうはアメリカ大陸、という感覚だったそうです。

8. 和歌山のみかん

スティーブストンで働き始めた日本人は、冬になると和歌山の家族からみかんを送ってもらいました。お正月に家族で食べたり、鏡餅にあしらったりしたのでしょう。

和歌山は、紀州とも呼ばれます。江戸時代、和歌山地域は紀州みかんと呼ばれる小さな甘いみかんでとても有名でした。19世紀後半には、これと並んで種のない温州みかんの栽培も盛んになっていました(関係記事『サツマみかんとは何か?』をご参照ください)。

スティーブストンで、お国自慢のみかんを友人やお世話になった人に分けたり、贈ったりしたことが、カナダのクリスマスオレンジの習慣と結び付きました。

1891年には早くもカナダの貿易会社が日本のみかんの輸入を始めています。みかん船の来航は、第二次大戦中とその後数年を除いて毎年続きました。こうして長い間、バンクーバー港に入る日本の船がクリスマス・シーズンの風物詩のようになったのです。

9.スティーブストンの子どもや孫たち

ところで、明治時代に働き始めた出稼ぎ者はもちろんのこと、初めてスティーブストンで生まれ育った子供たちも、カナダの学校に入ると、英語に苦労しました。裏を返せばこの人々は日本語が母語だったため、三尾の親戚との間には手紙や贈り物のやり取り、訪問など、太平洋をはさんで交流がありました。

一方、渡航者の孫の世代になると、英語が第一言語で、自分はカナダ人だと考えます。アジア系の移民がカナダ社会に完全に受け入れられるには時間がかかりましたが、第二次世界大戦後、日系カナダ人も選挙権など完全な市民権を得ることができました。また、戦時中の日系人の扱いについてカナダ政府から戦後補償・謝罪も行われました。

より新しい世代の日系カナダ人は、三尾などの日本の村が自分のルーツだと知っていて、旅行で訪れることはあります。でも、もはや親戚との個人的な交流はほとんどないようです。言葉が通じないためです。

10.工野儀兵衛

三尾の村人たちをスティーブストンに誘った大工の棟梁の名は、工野儀兵衛。

スティーブストンで日本人が出稼ぎをする環境を整えた功績で知られ、カナダ移民の父ともv呼ばれます。ほぼ20年、渡航者の世話をしつつ、日本食料品店兼下宿を経営していました。

儀兵衛は三尾からスティーブストンへの最初の移民となりましたが、和歌山に妻と子供を残した状態で移民し、カナダでの仕事にあまりに精力を傾けたので、一時帰国した時、妻はすでにほかの男性を夫としてしまっていたといいます。

カナダの冬は厳しい。やがて儀兵衛はリューマチを患いました。

症状が悪化し、57歳の時、事業を親族に引き継いで帰国。その6年後、1917年に和歌山で亡くなりました。最期までもう一度、懐かしいスティーブストンを訪れたいと言っていたそうです。

11.二つの村の資料館

あるウェブサイトで、19世紀末三尾出身の出稼ぎ者の孫である日系カナダ人が、2009年に三尾を訪ねた時の話を読みました。曰く、

三尾の緑豊かな山々は入り江まで迫り、ブリティッシュ・コロンビアの森林に覆われた山々が太平洋岸沿いにそそり立つ様を彷彿とさせた。三尾の出稼ぎ者たちはきっとスティーブストンの風景に親近感を覚えただろうと。

この人が立ち寄った三尾の「カナダ資料館」には、人々が持ち帰ったいろいろなものが展示されていました。古いトランク、フランネルの作業シャツ、台所用具、古い写真、子どもの作文、第二次大戦中に日系人収容所に強制収容された際に与えられた服などが出稼ぎ中の生活を物語り、カナダ先住民のトーテムポールなどまでありました。展示の目的は出稼ぎ者の生活の苦労を語り継ぐこと。説明は日本語だけだったようです。

「カナダ資料館」は2015年に閉館し、2018年7月に別の団体が、同様にカナダ移民にちなむ資料館「カナダミュージアム」を開館しました。これはスティーブストンから戻った人が建てた瀟洒な洋館をきれいに補修したものです。また、ウエブサイトは日本語のみだと思います(2021年5月現在)。

一方、スティーブトンにも、小さな歴史的建造物 Japanese Fishermen’s Benevolent Society Buildingが残っています。また、カナダ政府、カナダ移民博物館、全カナダ日系人協会、カナダの日本語メディア、ローカルメディアなど、英語が多いですが、日本語でも、工野儀兵衛や日系カナダ移民の歴史を語り継いでいます。

日本からのカナダ移民について、興味深い話がたくさんありました。いつか三尾やスティーブストンを訪れて、他の話も聞きたいものです。

[和文終わり]

References / 参考資料

- 財務省貿易統計, customs.go.jp

- 平間俊行,「クリスマス・オレンジ」, カナダシアター, https://www.canada.jp/stories/post-3275/

- ‘Here’s why Canadians eat mandarin oranges during the holiday season’, Vancouver Is Awesome, https://www.vancouverisawesome.com/sponsored/christmas-orange-history-canada-1969152

- ‘Christmas oranges: Local history advent calendar 2018-Day 24, Mandarin oranges’, Vanalogue, Dec. 24, 2008, https://vanalogue.wordpress.com/tag/christmas-oranges/

- ‘Japanese Canadian History’, National Association of Japanese Canadians, http://najc.ca/japanese-canadian-history/

- 「日系カナダ人の歴史」, 全カナダ日系人協会, http://najc.ca/日系カナダ人の歴史/

- ‘Gentlemen’s Agreement, 1908’ (Hayashi-Lemieux Agreement), Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, https://pier21.ca/research/immigration-history/gentlemens-agreement-1908

- Akemi Kikumura Yano, ‘Canada-Migration Historical Overview’, Discover Nikkei, 28 Mar 2014, http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2014/3/28/canada/

- アケミ・キクムラ・ヤノ,「日経カナダ移民略史」, ディスカバー・ニッケイ, 2014年3月28日, http://www.discovernikkei.org/ja/journal/2014/3/28/canada/

- ‘How BC’s Multicultural Fishing Industry Shaped the Province (Photos)’, Vancouver Is Awesome, May 18, 2017, https://www.vancouverisawesome.com/history/how-bcs-multicultural-fishing-industry-shaped-the-province-photos-1933780

- 「日本人初移住から140年。カナダ・スティーブストンの魅力」, テレビジャパン, 2017年10月20日, https://tvjapan.net/post/カナダ-日系人ゆかりの街、バンクーバーの郊外/

- 「アメリカ村 (美浜町)」, https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/アメリカ村_(美浜町)

- 河原典史,「日系カナダ移民のライフヒストリーをめぐる調査法の再考」, http://www.ritsumei.ac.jp/acd/re/k-rsc/lcs/kiyou/17-4/RitsIILCS_17.4pp.3-20Kawahara.pdf

- 椿真智子,「多文化社会カナダにおける日系人社会の変容と文化継承」, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/15917179.pdf

- 在バンクーバー日本国総領事館開館125周年記念フォーラム「二つの歩み」日本外交と日系人の遺産第2回「家族移民と日系コミュニティーの拡大:20世紀初頭~戦前」,『バンクーバー新報』, http://www.v-shinpo.com/special/1306-2014-01-24-20-14-54-36425785

- 在バンクーバー日本国総領事館開館125周年記念フォーラム「二つの歩み」日本外交と日系人の遺産第3回「第二次世界大戦時代」, 『バンクーバー新報』, http://www.v-shinpo.com/special/1346-2014-01-24-20-14-54-36425796

- 在バンクーバー日本国総領事館開館125周年記念フォーラム「二つの歩み」日本外交と日系人の遺産第4回「戦後復興時代」, 『バンクーバー新報』, http://www.v-shinpo.com/special/1349-2014-01-24-20-14-54-3642579718

- 在バンクーバー日本国総領事館開館125周年記念フォーラム「二つの歩み」日本外交と日系人の遺産総括バンクーバー日本人学校創立と時代背景, 『バンクーバー新報』, http://www.v-shinpo.com/special/1544-2014-01-24-20-14-54-36425831

- 在バンクーバー日本国総領事館開館125周年山田千佳子記念講演会, 『日系カナダ人の歴史~海を渡った日本の村、三世代の変遷の物語~』講演要約, 『バンクーバー新報』, http://v-shinpo.com/special/1367-2014-01-24-20-14-54-36425801

- Gerry Shikatani, ‘Easts Meets West; Why Japanese fishing village proudly flies a Canadian flag’, Winnipeg Free Press, May 16, 2009, https://www.vancouverisawesome.com/sponsored/christmas-orange-history-canada-1969152

- ‘The Steveston Museum’, Tourism Richmond BC, https://www.visitrichmondbc.com/listing/the-steveston-museum/50/

- ‘Japanese Fishermen’s Benevolent Society Building Exhibit’, Steveston Historical Society, 6 June 2015, http://historicsteveston.ca/japanese-fishermens-benevolent-society-building-exhibit/

- 「和歌山・美浜にカナダミュージアム カナダ移民の功績を紹介」, 和歌山経済新聞, 2018年8月28日, https://wakayama.keizai.biz/headline/1182/

- 「工野儀兵衛のひ孫髙井さん、母の肖像画を移民資料館に寄贈」, 日高新報, 2020年7月4日, https://www.hidakashimpo.co.jp/news1/2020/07/工野儀兵衛のひ孫髙井さん%E3%80%80母の肖像画を移民資.html

- 「アメリカ村資料館(日ノ岬パーク)」, 癒しの和歌山, 2011年8月22日, https://ameblo.jp/968-910/entry-10995992178.html