The Katakana That Disappeared

ルビ付きの和訳が英文の下にあります。 / Japanese translation with Ruby is on the bottom of this page.

Contents

- A katakana that disappeared

- What is “ヴ”?

- Words with “va” “vi” “vu” “ve” “vo”

- A change in the spelling system

- The transition of “v” to “b”

- The remains of the old spelling

- MoFA and the katakana that disappeared

- “ヴ” can be very important to some

- “ヴ” in today’s Japanese

- japanese translation

***********************************

1. A katakana that disappeared

From April 1, 2019, the character “ヴ (pronounced “vu”)” in foreign country names disappeared from official documents of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA).

You may have seen the katakana “ウ” (“u”), but did you know another katakana, “ヴ”?

2. What Is “ヴ”?

“ヴ” is a katakana created near the end of the Edo Era.

At that time, the Japanese people had re-discovered Western culture. It was a huge collection of information, and much of it had not been available to them through the meager communication with Holland allowed by the Tokugawa Shogunate.

As the Japanese tried to learn about and from the West, they found that many Western words contained “v” whose sound didn’t exist in Japanese then.

Therefore, Fukuzawa Yukichi, an educator, proposed to use new characters “ヷ”, “ヸ”, “ヴ”, “ヹ”, “ヺ”, to express “va”, “vi”, “vu”, “ve”, and “vo” respectively. He just added two very short lines on the top right of existing katakana, “ワ (pronounced “wa”)”, “ヰ (pronounced “i” today)”, “ウ (“u”)”, “ヱ (pronounced “e” today)” and “ヲ (“o” or “wo”)”.

That is how “ヴ (vu)” was born.

3. Words with “va” “vi” “vu” “ve” “vo”

Well known examples with these characters include:

- ヷイマール (Vaimaaru for Weimar)

- ヸオロン (vioron for violin in French)

- ヴロンスキー (Vuronskii for Vronsky in “Anna Karenina”)

- 『ヹニスの商人』 (“Venisu no shoonin” for “Merchant of Venice”)

- ヺルガ (Voruga for the Volga, the longest river in Russia)

4. A change in the spelling system

After WWII, there was a big education reform in Japan. In 1947, new spelling rules were enforced and as a result, “ヷ”, “ヸ”, “ヹ” and “ヺ” went out of use.

As for “ヴ”, it stayed, but it was used in a different way.

In the new spelling system, “ヴ” had two pronunciations. When we read it alone, we pronounced it “vu”. However, if we saw it followed by another character such as “ァ (“a”)”, “ィ (“i”), “ェ (“e”)”, “ォ (“o”)”, or “ュ (“yu”)”, it stood for “v” and as a combination we read it “ヴァ (“va”)”, “ヴィ (“vi”)”, “ヴェ (“ve”)”, “ヴォ (“vo”)” or “ヴュ (“vyu”)” as one mora.

5. The transition of “v” to “b”

During the subsequent decades, the Japanese borrowed a huge number of words from English and began to use them in everyday life.

Some words were spelled with “ヴ” such as in “テレヴィジョン (“terevijon” for television)”. However, the use of “バ (“ba”)”, “ビ” (“bi”), “ブ (“bu”), “ベ (“be”)”, “ボ (“bo”)” in place of “ヴァ (“va”), “ヴィ (“vi”)”, “ヴ (“vu”)”, “ヴェ (“ve”)”, “ヴォ (“vo”)” has become increasingly common.

With the “b” sound, we feel that the word has truly become a part of Japanese. Now we call a TV set “テレビ” only.

Other such examples:

- バニラ (“banira” for vanilla)

- ビニール (“biniiru” for vinyl)

- ソビエト (“sobieto” for Soviet)

- ラブレター (“labu-retaa” for love-letter)

- エレベーター(“erebeetaa” for elevator)

- ボランティア(“borantia” for volunteer)

6. The remains of the old spelling

Even today, there are a lot of inconsistencies in the spelling of loan words. It seems some old spellings still remain.

With regard to some words borrowed or transcribed from German, Russian, etc.:

- We often spell “va” as “ワ”. Example: ワイマール (“Waimaaru” for Weimar), ワルシャワ (“Warushawa” for Warsaw), モスクワ (“Mosukuwa” for Moskva, meaning Moscow), ワルワーラ (“Waruwaara” for Varvara, a woman’s name), ワクチン (“wakuchin” for vaccine)

- We sometimes spell “v” at the beginning of a word as “ウ (“u”)”. Example: ウラジミール (“Urajimiiru” for Vladimir)

- There is an example to spell “vo” as “オ (“o”)”: ウラジオストック (“Urajiosutokku” for Vladivostok)

It seems that words such as the old “ヴァイマール”, “ヷルヷーラ”, “ヴラジヺストック” had been so popular that even after the spelling reform of 1946 people kept using the same characters without the short lines. They could still recognize the meaning easily.

We hope to keep looking for information on the transition in spelling of loan words.

7. MoFA and the katakana that disappeared

After WWII, the MoFA tried to spell the names of foreign places as closely to the original pronunciation, or sometimes English pronunciation, as possible.

Naturally, they frequently used “ヴ (“v” or “vu”)” in the new spelling system.

However, no name with “ヴ” became truly popular. People always called Vietnam “ベトナム” (Betonamu) and never “ヴェトナム (Vetonamu)”.

About the year 2000, finally, the MoFA began to discuss the use of country names that Japanese citizens would understand easily and could adopt in their lives. They researched dictionaries and books that people frequently referred to, and found out “ヴ” was actually very little used.

So, they replaced “ヴァ (“va”)”, “ヴィ (“vi”)” , “ヴ (“v”)” , “ヴェ (“ve”)” and “ヴォ (“vo”)” with “バ (“ba”)”, “ビ (“bi”)”, “ブ (“bu”)”, “ベ (“be”)” and “ボ (“bo”)”, one by one, in their official documents.

As a result, as of March 31, 2019, there were finally only two countries whose names contain “ヴ”. They were St. Christopher Navis and Cabo Verde. From April 1, in the MoFA websites, they appear as “セントクリストファー・ネービス (“Sento Kurisutofaa Neebisu”)” and “カーボベルデ (“Kaabo Berude”)”.

8. “ヴ ” is very important to some

On the other hand, some people received the news of the MoFA’s spelling policy change with dismay.

Among them were fans of the popular animation “ヱヴァンゲリヲン(“Evangerion”) and the professional basketball team “熊本ヴォルターズ (“Kumamoto Volters”)”. They feared that their beloved animation and the team had to change the names to plain “エバンゲリオン (“Ebangerion”)” and “ボルターズ (“Boltaazu”)” with the commonplace “b” sound. Some even inquired to NHK (Japan’s National Broadcasting Corporation) and National Institute for Japanese Language about it.

Of course, the use of “ヴ” outside the MoFA will be intact.

9. “ヴ” in today’s Japanese

In today’s Japanese, we often see “ヴ” in words when their foreign origin is stressed.

Examples:

- ヴィネグレット (vineguretto for vinaigrette)

- ルイ・ヴィトン (Rui Viton for Louis Vuitton)

- オーボンヴュータン (Oobonvyuutan or Au Bon Vieux Temps, a pastry shop in Tokyo)

- ヴェネツィア (Venezia or Venice)

- ヴォーグ (Vogue, the magazine)

However, in reading these words, we unconsciously change the “v” to “b”. In other words, we actually say “bineguretto”, “Biton” and so on. The “v” sound is so unfamiliar that even today people refer to the alphabet “V” as “bui (pronounced like “buoy”)”.

Then, why use “ヴ”?

If someone uses “ヴ”, the speaker could sound more cultivated; the thing could look more beautiful or expensive; or they could impress some young people or some people who yearn for the foreign culture.

Looking back at its history, Japan has always respected foreign-born things. Even the people were not very interested in speaking a foreign language, they have always cherished using loan words.

It seems that “ヴ” reflects our such attitude as that.

[The end of the English post]

****************************************

消えた片仮名

目次

- 消えた片仮名

- “ヴ” とは?

- ヷ行の言葉

- 仮名遣いの変化

- バ行への置き換え

- 旧仮名遣いの名残

- 外務省と消えた片仮名

- 「ヴ」が大切な人々も

- 現代の日本語と「ヴ」

****************************************

1.消えた片仮名

2019年4月1日より、片仮名「ヴ (“vu” と読む)」が外務省の文書の外国名からなくなりました。

片仮名の「ウ」は見たことがあると思いますが、「ヴ」って、見たことありますか?

2. “ヴ” とは?

「ヴ」は江戸時代末期に創られた片仮名です。

当時、日本人は西洋文化を再発見したところでした。そこには、幕府に制限されたオランダとの関係からは得られなかった、膨大な量の情報があったのです。

日本人は西洋について、そして西洋から学ぶ過程で、西洋の言葉には当時の日本語にはなかった音を表す “v” がたくさんあるのに気づきました。

そのため、福沢諭吉という教育者が既存の片仮名「ワ」「ヰ (現在はイと読む)」「ウ」「ヱ (同 エ、イェなどと読む)」「ヲ」の右肩に短い線を二つ付けて、「ヷ (“va” と読む)」「ヸ (“vi”)」「ヴ (“vu”)」「ヹ (“ve”)」「ヺ (“vo”)」という新しい文字で “v” の音を表すことを提唱しました。

それが、今日使われている「ヴ」の始まりです。

3. ヷ行の言葉

下は、これらの文字のよく知られた用例です。

- ヷイマール (Vaimaaru、Weimar のこと)

- ヸオロン (Vioron、フランス語でバイオリン violon のこと)

- ヴロンスキー (Vuronskii、『アンナ・カレーニナ』の登場人物 Vronskyのこと)

- ヹニスの商人 (『Venisu の商人』、“Merchant of Venice” のこと)

- ヺルガ (Voruga、ロシアの大河 Volga のこと)

4. 仮名遣いの変化

第二次世界大戦後、大きな教育改革がありました。1947年に、新しい仮名遣いの規則が発効し、「ヷ」「ヸ」「ヹ」「ヺ」は使われなくなりました。

「ヴ」は残りましたが、違う使い方になりました。

それによれば、「ヴ」は発音が二つあります。「ヴ」の字だけを読むときは、”vu” と読みます。しかし、「ァ」「ィ」「ェ」「ォ」「ュ」など他の字が後につくときは、ただの “v” を表し、それらの字と併せてセットにして、それぞれ「ヴァ (va)」「ヴィ (vi)」「ヴェ (ve)」「ヴォ (vo)」「ヴュ (vyu)」と、モーラひとつ分として読むのです。

5. バ行への置き換え

続く20世紀後半、日本人は英語から膨大な数の言葉を借用するようになりました。

“V” があって「テレヴィジョン」のように「ヴ」を使う言葉もありましたが、そのうち「バ」「ビ」「ブ」「ベ」「ボ」が「ヴァ」「ヴィ」「ヴ」「ヴェ」「ヴォ」にとって代わることが多くなりました。

バ行が使われていると、その言葉が日本語に馴染んでいる感じがします。「テレヴィ」は「テレビ」になりました。他にも、同じような例がたくさんあります。

- バニラ (vanilla)

- ビニール (vinyl)

- ソビエト (Soviet)

- ラブレター (love-letter)

- エレベーター (elevator)

- ボランティア (volunteer)

6. 旧仮名遣いの名残

現在でも、外来語の書き方には一貫性がありません。中には、旧仮名遣いも含まれているようです。

ドイツ語、ロシア語などから入ってきた言葉は、今でも‥‥

- “Va” を「ワ」と書くことがあります。例:ワイマール (Weimar)、ワルシャワ (Warsaw)、モスクワ (Moscow)、ワルワーラ (Varvara、女性の名前)、ワクチン (vaccine)

- 語頭の “v” を「ウ」と書くことがあります。例:ウラジミール (Vladimir)

- 語頭の “vo” を「オ」とする例があります。例:ウラジオストック (Vladivostok)

昔の「ヷイマール」「ヷルヷーラ」「ヴラジヺストック」などが日本語に非常に馴染んでいて、1946年の仮名遣い改定後も、濁点を落としたままで使い続けたように思えるのです。濁点なしでも、意味は十分通ります。

この間の状況については、今後も興味を持っていたいと思います。

7. 外務省と消えた片仮名

第二次世界大戦後、外務省はできるだけ原音または英語に近い音で外国の地名を表記しようとしました。

当然、新しい仮名遣いによる「ヴ」も多用しました。

しかし、「ヴ」のついた国名は日本人の生活には定着しませんでした。私たちにとってはベトナムはいつも「ベトナム」で、「ヴィエトナム」ではなかった。

西暦2000年ごろ、外務省はやっと国民に分かりやすく、日常生活になじみやすい国名表記を検討し始めました。そのために職員が辞書や参考文献をいろいろ調べてみると、「ヴ」はほとんど使われていませんでした。

そこで、外務省の文書では「ヴァ」「ヴィ」「ヴ」「ヴェ」「ヴォ」が少しずつバ行へと変更され、その結果、2019年3月31日の時点で、「ヴ」の残っている国名は二つだけとなっていました。

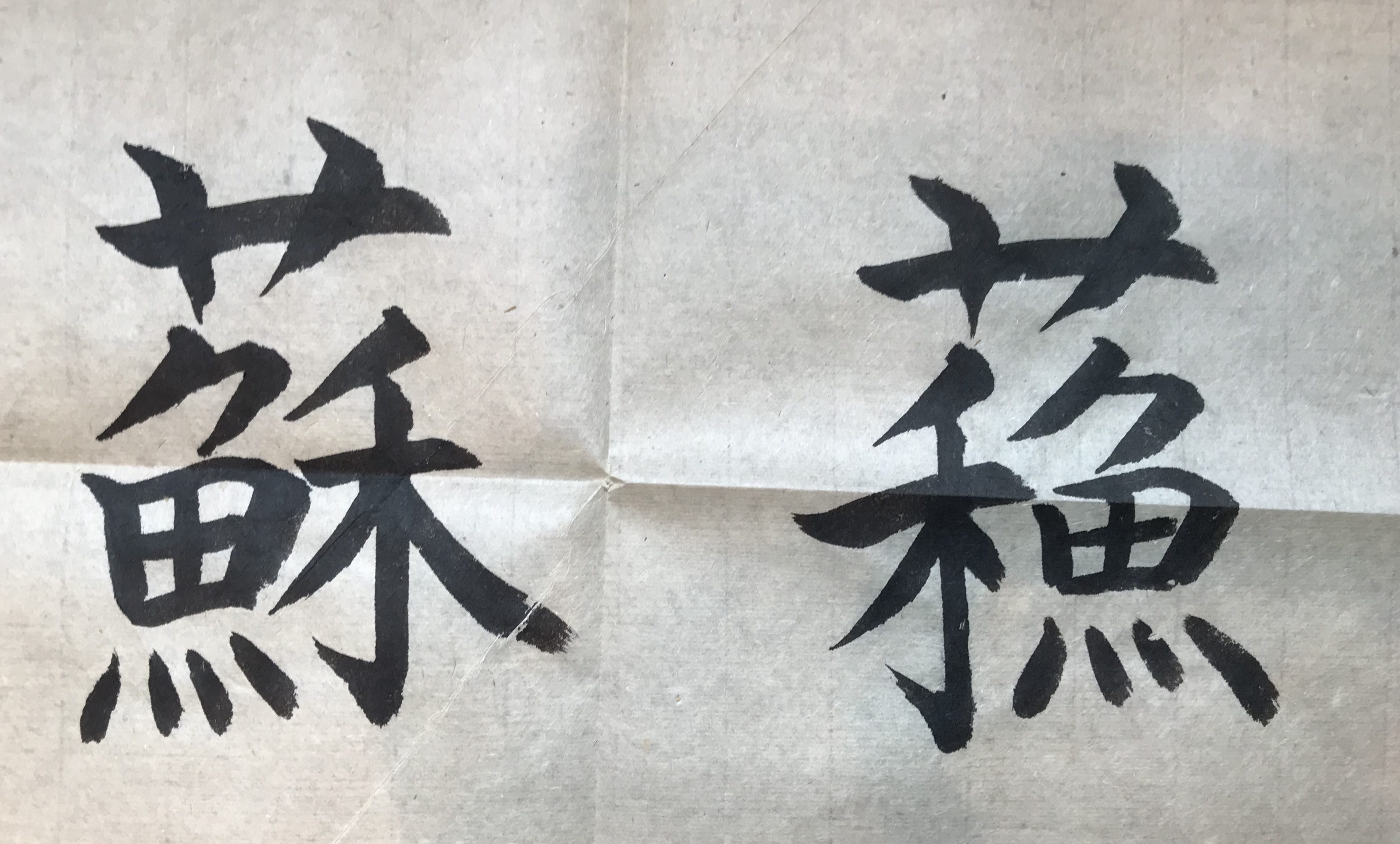

それが、写真のセントクリストファー・ネーヴィスとカーボヴェルデなのです。

4月1日から、これらの国名は「セントクリストファー・ネービス」 と「カーボベルデ」と書かれることになりました。

[2019年4月2日外務省のウエブサイトで改訂を確認しました。]

8.「ヴ」が大切な人々も

一方、外務省の仮名遣い変更のニュースに落胆した人々もいました。

アニメ「エヴァンゲリヲン」やプロバスケットボールチーム「熊本ヴォルターズ」のファンなどは、今後愛するアニメや贔屓のチームの名前がただのバ行の「エバンゲリオン」「熊本ボルターズ」になるのかと心配しました。NHKや国立国語研究所に問い合わせた人もいるそうです。

もちろん外務省とは関係なく、「ヴ」の一般的な使用はこれからも続くでしょう。

9.現代の日本語と「ヴ」

現代の日本語で、「ヴ」の付いた言葉は、特に以下のように外国の出自をはっきりさせたい時によく見かけます。

- ヴィネグレット (vinaigrette)

- ルイ・ヴィトン (Louis Vuitton)

- オーボンヴュータン (Au Bon Vieux Temps、東京の有名なパティスリー)

- ヴェネツィア (Venezia)

- ヴォーグ (Vogue、雑誌の名前)

しかし、これらの言葉も、日本人が話すときは無意識に “v” を “b” に読み替えています。つまり、「ビネグレット」「ビトン」などと言うし、アルファベットの “V” も、「ブイ」と読むのです。

それなら、なぜあえて「ヴ」を使うのか?

「ヴ」を使うと、発信者に教養があるように見えたり、言葉の表すものがより素晴らしく、または高級そうに見えたり、若い人や外国文化に憧れる人々の一部に訴える可能性があったりするためです。

昔から、日本では外国から渡来したものを珍重し、外国語を話すことにはあまり興味がなくても、外来語を大切にしてきました。

「ヴ」は、私たちのそのような感覚を反映しているようです。

[和文部終わり]

[print-me]